Orthodontic retention is well accepted as being required post orthodontic treatment in-order to prevent undesirable tooth movement. In recent time it has become recommended that retention following orthodontics is a lifelong necessity in-order to maintain the orthodontic outcome. However, as the cause of lifelong tooth movement affects everyone should we be looking at retention to prevent restorative problems developing or progressing – Should we be retaining for prevention?

Firstly, it is important to understand that tooth movement occurs throughout life as a natural phenomenon. This mainly affects the lower arch resulting in a reducing arch length, collapse of the inter-canine width and crowding of the anteriors. This is a combination of mesial drift (the process that is thought to allow for interproximal wear occuring in an abrasive a stone age diet), facial growth occurring throughout life and soft tissue age changes (reduction in muscle tone and flexibility). The combined effect on the dentition is similar to blocking the end of a travelator, in that the forward moving teeth crowd up against the ‘barrier’ of the lips.

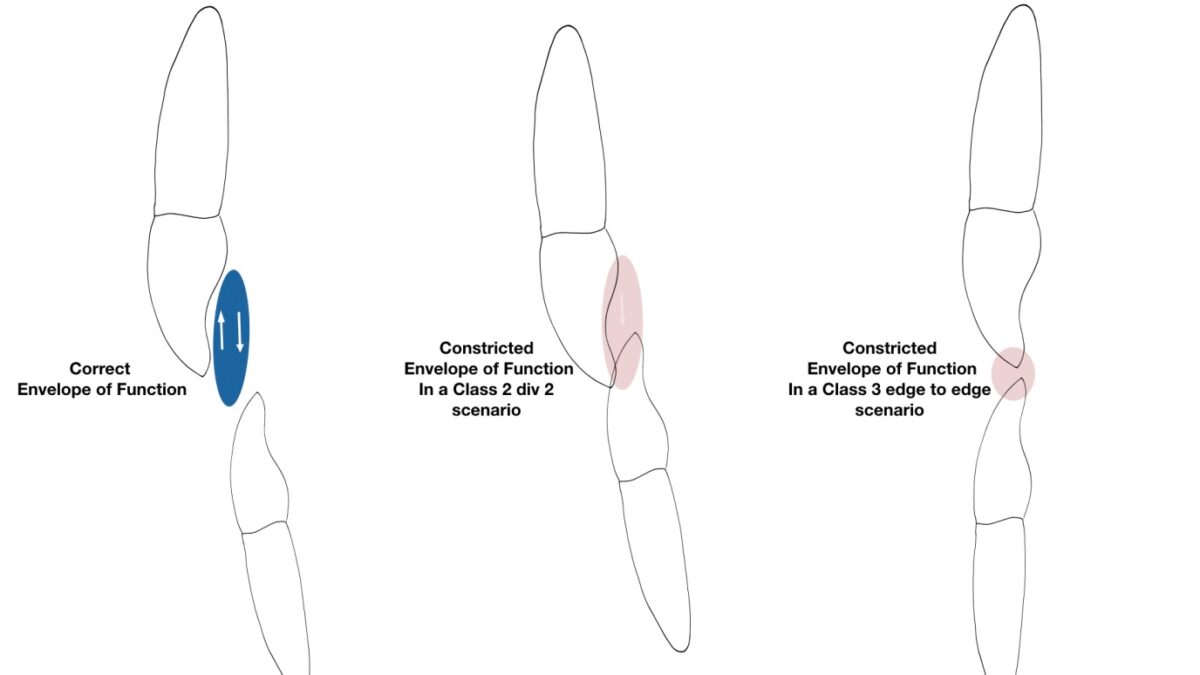

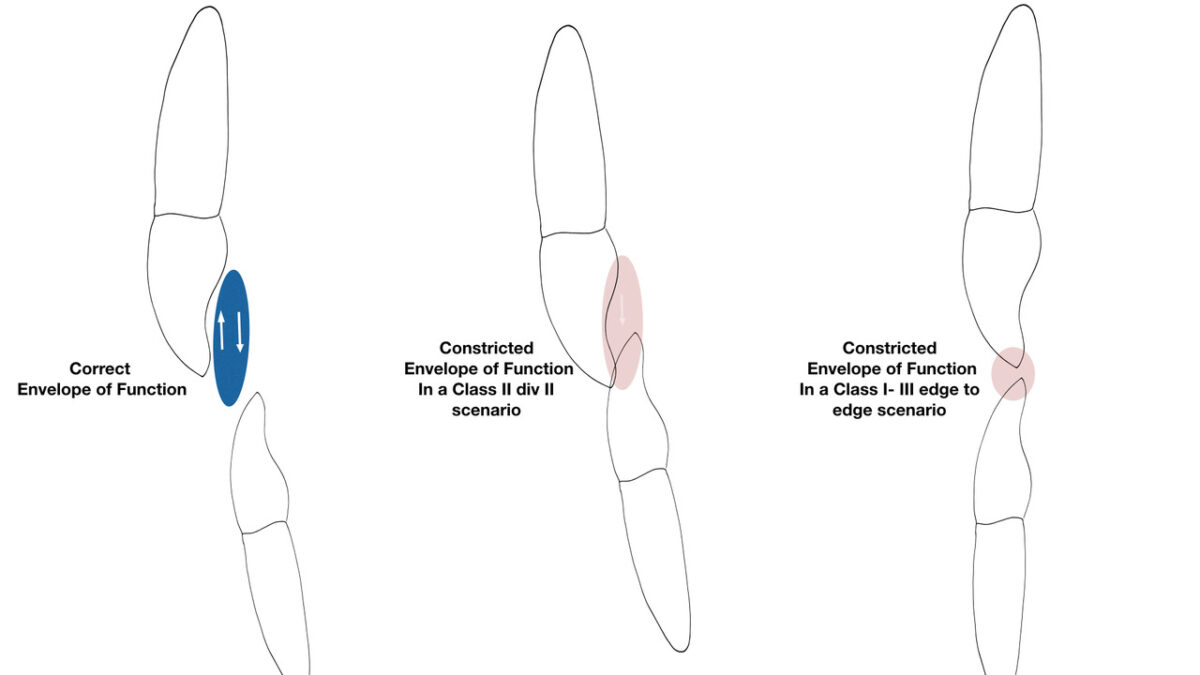

This crowding result in reducing the ‘Envelope of Function’ a concept first described by Pete Dawson 5 (Figure 1) and ‘Pathway Wear’, described by Greggory Kinzer 6 (Figures 2 and 3). The combination of continued tooth movement, the dynamics of the envelope of function and pathway wear means that a patient’s anterior tooth position changes with time but the patient’s pattern of function or parafunctional movements do not.

The lower teeth moving forward at a greater rate than the uppers as a natural phenomenon and the result of this constricts the Envelope of Function resulting in the wear of upper and lower incisal edges. This can lead to chipping of the incisal edges and continued wear occurring.

The patient in Case 2 shows how lower incisor crowding develops with time. The upper image in Figure 7 shows when the patient first presented with minimal lower incisor crowding and no upper anterior wear. The lower image (Figure 7) is 3 years later showing how mesial drift and collapse of the inter-canine width has resulted in reduced overjet and a constricted envelope of function which resulted in wear of the upper anteriors.

The failure is due the to the lower anterior teeth functionally occluding on the incisal edge of the uppers, resulting in wear and chipping. When the uppers are restored, the undiagnosed occlusal forces result in failure of the composite. Then, with porcelain being used, the lower anteriors begin a destructive cycle of incisal wear, with significant loss of lower incisor crown height and overeruption of the lower incisors. Eventually, becoming a difficult problem to correct.

Too often dental practitioners observe and passively monitor this collapse and resulting incisal wear. Hence, patients and clinicians complain that new upper anterior composite restorations keep failing. Despite using the best techniques and multiple repairs the restoration repeatedly fails. But, instead of asking why is this occurring, the clinician tends to resort to more and more destructive means of restoring the anterior teeth. Resulting in veneers and then crowns, whilst not diagnosing or understanding the cause.

Parts of the profession have grasped the concepts, understanding that functional and occlusal change can come from continued tooth movement. Orthodontists have long known that teeth move throughout life and recognise the problem. When this occurs in late teens and early adulthood it is referred to as ‘late lower incisor crowding’ or ‘orthodontic aging’. This is not just a young person’s problem. Teeth move forward throughout life due to mesial drift and combined with biological age related soft tissue changes, this result in lower incisor crowding and collapse of the lower inter-canine width. Little et al’s 1,2,3 studies following post orthodontic treatment retention found that with or without orthodontic treatment the lower incisors undergo movement, relapse and crowding with time. Little et al 2 also reported in 1981, that 10 years after retainers are ceased 70% of cases needed re-treatment. The concept of continued tooth movement is supported by Yuko Saito et al 4 work into age-related changes in patients with untreated Angle Class 1 crowding. They reported that anterior crowding increases with age due to a decrease in the length of the maxillary arch as well as a decrease in anterior arch width especially in the mandibular region. Their study found that patients with un-treated crowding displayed increased maxillary crowding, with mandibular crowding increasing in both treated and un treated cases.

This knowledge of lower crowding has been around for quite some time, but it is more recently with Dawson and Kinzer that the effect on restorative care has become more widely accepted.

The problem of not closely monitoring patients for changes in tooth position and/or wear over long time period is a problem both in general practice and in orthodontics. Very few orthodontists are in the position to follow treated patients for life. It is simply not practical that orthodontists to monitor all their patients for life. It appears to be, globally orthodontics is carried out in isolation; treatment is completed, retention is provided and monitored for a relatively short time period (1-2 years). Then the patient is passed to the general practitioner who often has a poor understanding of retention 7, possibly with limited or no funded maintenance, or the skills to maintain the aligned teeth. Equally, few general partitioners monitor changes in tooth position or wear and even fewer appear to recognise the significance when crowding results in tooth wear.

Case 1 shows a typical reduction in the Envelope of Function case where the patient has had number of repeatedly failing upper anterior restorations over the years, to the extent that the patient had been informed the only option was full crowns. At first glance (Figure 4) it appears a simple case of larger and more robust restorations being required i.e. crowns or veneers. However, when the occlusion is examined (Figure 5) the lower crowding and cause of wear is obvious. The occlusal changes from tooth movement as resulted in a constricted envelope of function and wear/chipping of the uppers. This in turn leads to restorations that are doomed to failure because of the occlusion. If this case had been treated as originally been proposed with no action being taken to correct the lower tooth position the constricted envelope of function would have resulted in further failure. Figure 6 shows the outcome of simple lower orthodontic alignment using an Inman Aligner, interproximal reduction to provide space and minimally invasive composite restoration of the incisal edges.

With longitudinal records (photographs and /or 3D scans/impressions) tooth movement and potential of incisal wear can be simply monitored and early intervention initiated. This means we should be in a position to offer orthodontic retention to all patients either before or as soon as anterior collapse has been diagnosed as Prevention is better than Cure. In addition, the use of appropriate orthodontic appliances to realign slightly misaligned anteriors, possibly with interproximal reduction to create space, followed by lifelong retention will prevent many mid and late life wear problems. These are simple skills that all dentists should have access to and if there are concerns, an orthodontic referral is appropriate.

What is the best Retention for Prevention?

The evidence is rather poor 8 and many studies comparing retainer types are of short duration. It would appear that fixed retention is slightly better than removable and a Vacuum Formed Retainer (VMR, commonly known as an ‘essix’ retainer) is better than a Hawley or similar removable appliance retainer. As to the amount wear required, the evidence is that 24-48 hours initially following removal of appliances then nights only is more than sufficient. Our experience is that following orthodontic treatment, that after the first year of wearing the VFR at night, careful reduction to 2-3 nights wear each week is sufficient for the majority of patients. However, a few will require wear every night. The message being “You can wear a retainer too little, but cannot wear it too much”

As to what type of retainer to recommend either following orthodontic treatment, or to prevent further tooth movement it seem reasonable to propose that “dual retention” ie both fixed and VFR should provide the best all round retention regime. However, each individual patient’s needs require assessing and discussion to make the best choice for the individual.

The profession needs to act on the current evidence on tooth movement and tooth wear with both undergraduate and postgraduate education changing to reflect this. As part of these changes, retention should not be just considered an option for the post orthodontic patient. Training needs to educate dentists in recognition of tooth movement, occlusal change, along with training in placement and management of retainers. Ideally that limited training in simple realignment of minimally crowded cases using easy to use appliances e.g., aligners, would be an appropriate skill for all dentists to acquire.

However, there are still significant gaps in knowledge and better evidence is required as the understanding of tooth stability, the consequences of long-term retainer wear (10+ years) and the best form(s) of retention. In addition, more studies are needed to understand how and why teeth crowd and the consequential occlusal changes. For example, if we know that lower anterior teeth will crowd, we need to understand what the resultant affect is on the overjet reducing or enlarging in a variety of situations. Logically a reducing overjet can cause increased risk of pathway wear

Theses unknown, unknowns need answering.

Dentists who see patients over long time periods will recognise the results of relapse or continued tooth movement results in more than just cosmetic problems. Collapse of canine width, loss of guidance, constricting envelopes of function, tooth wear, deepening bites, fremitus and bone loss can develop due to continued tooth movement.

Does this mean that all general dentists should be able to carry out orthodontics and or provide retention for every patient on every patient? Absolutely not.

Appropriate orthodontics carried out by the general practitioner with the aim to align teeth for cosmetic and wear prevention, enables minimally invasive restorative care. Correct use of preventive retention will stop constriction of the envelope of function and wear occurring.

Hence, we believe that orthodontic retention is an essential tool in restorative patient care.

References

1. Little RM.

Stability and relapse of dental arch alignment.

Br J Orthod. 1990 17:235-41

2. Little RM. Wallen TR, Riede RA

Stability and relapse of mandibular anterior alignment-first premolar extraction cases treated by traditional edgewise orthodontics

Am J Orthod 1981, 80; 349-65

3. Little RM, Riedel RA Artun

An evaluation of changes in mandibular anterior alignment from 10 to 20 years postretention.

J. Am J Orthod 1988 93: 423-8

4. Yuka Saito, Aiko Tanoi, Etsuko Motegi and Kenji Sueishi

Changes in anterior crowding over 20 years from Third Decade of Life in Untreated Angle Class 1 Crowding

Bull Tokyo Dent Coll 2019 60:163-176

5 Dawson PJ.

Evaluation, Diagnosis and Treatment of Occlusal Problems.

2nd edition. 1989; 20:369-370.

6 Greggory Kinzer

Managing failures due to pathway wear Part I/II

Spear education July 2013

7. S. Kotecha, S. Gale, L. Khamashta-Ledezma, J. Scott, M. Seedat, M. Storey, A. Ulhaq and J. Scholey

A multicentre audit of GDPs knowledge of orthodontic retention

Br Dent J 2015 218; 11. 650-653

8. Littlewood SJ, Millett DT, Doubleday B, Bearn DR, Worthington HV.

Retention procedures for stabilising tooth position after treatment with orthodontic braces. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD002283. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002283.pub4. Accessed 02 December 2020